Published on stuff

By Mandy Te

05:00, Feb 08 2021

Debbie Donnelly’s mother Setsuko moved to New Zealand from Japan in the 1950s. While she thrived and co-founded the Japan Society in Wellington, people were not always nice to her and at times, she was on the receiving end of racism.

The ‘forever foreigner’ concept is often only applied to migrants of colour, who then face social stigma, stereotypes and racism in Aotearoa. Mandy Te investigates the phenomenon and how it impacts on Kiwi who are made to feel like strangers in their own homeland.

As a group of Taiko drummers performed at a festival in Porirua, Debbie Donnelly remembers a stranger turning to her and saying “they’re not like us”.

Donnelly was the wrong person to pick out of the crowd. For most of her life, she has thought deeply about the duality of her identity.

When she was younger, people would tell her she had the best of both worlds when it came to being Japanese and Pākehā. At the time, she didn’t know what that meant.

Sitting in her Kāpiti home, there’s a glint in her eyes as she thinks about her identity, racism, and her mother, Setsuko.

Her parents, Setsuko, from the city of Takehara, and Mick, a Pākehā man, met in Japan through a Catholic priest.

Donnelly’s mother moved to Wellington in the 1950s, marrying Mick at St Anne’s Catholic Church in Newtown. The couple briefly lived in Masterton before moving to Wellington.

It was in the capital city that Setsuko thrived as an interpreter, meeting prime ministers and the Queen. She also became a co-founder of the Japanese Society.

Mick was supportive of Setsuko as she pursued her interests.

When it came to the racism, Donnelly says her mother protected her and her siblings from the details but she did share anecdotes.

“She felt she was a punching bag for a lot of people [and] a lot of people’s frustrations,” Donnelly says.

“At the time I could only imagine the culture shock combined with not knowing the language, not knowing what people are saying about you but knowing she wasn’t being welcomed.”

She believes the racism her mother experienced was linked to anti-Japanese sentiment following the war.

Donnelly’s brother, Leo, recalled a moment years after his mother’s death, when a woman approached him to apologise for how his mother was treated in Masterton.

“My mother didn’t put any blame on anyone, but she was happy to leave and that was probably because of the way in which she was spoken about,” Leo says.

As children, Donnelly and Leo recall experiencing racist taunts signalling to them that “you’re not us”.

The advice Leo got from his parents, and from his mother in particular, was about being resilient – she used The Great Wave off Kanagawa painting as an example.

She believes the racism her mother experienced was linked to anti-Japanese sentiment following the war.

Donnelly’s brother, Leo, recalled a moment years after his mother’s death, when a woman approached him to apologise for how his mother was treated in Masterton.

“My mother didn’t put any blame on anyone, but she was happy to leave and that was probably because of the way in which she was spoken about,” Leo says.

As children, Donnelly and Leo recall experiencing racist taunts signalling to them that “you’re not us”.

The advice Leo got from his parents, and from his mother in particular, was about being resilient – she used The Great Wave off Kanagawa painting as an example.

Photo supplied by Donnelly family.

“It was not what people thought it may mean which was ‘you can’t beat the force of nature’, it was the fact you bow to the wave but you don’t go under,” Leo says. “There’re some things you can’t control but you stay afloat. You work your way up and you work your way through those situations.”

Nowadays, he sees similar attitudes to the ones he encountered when he was younger come up in pockets – like how Asian people were treated during the Covid-19 pandemic.

When it comes to racism, he says, it’s about making it clear that it’s unacceptable while also providing support for people on the receiving end, to help them cope with the emotional impact.

“People act out of ignorance and fear but it still doesn’t make it right.”

While Setsuko never shied away from her Japanese roots, she considered New Zealand her home and herself a Kiwi.

Their mother’s experience of feeling like a “punching bag” and feeling unwelcome is not something she went through alone.

Photo supplied by Donnelly family.

Forever a foreigner

New and old migrants have gone through those feelings – many of it stemming from the concept of being treated as “forever a foreigner.”

Emeritus Professor Manying Ip has studied the “forever a foreigner” concept for decades, mainly in connection to Chinese New Zealanders.

Speaking to Chinese New Zealanders, she noted how they felt out of place – as if they didn’t belong.

Using a Chinese saying to define the concept, she says “forever a foreigner” is about people from minority groups feeling as though they are living under another person’s roof.

It was someone else’s place, not theirs, and they would never feel as though they belonged, she says.

Photo by LAWRENCE SMITH/Stuff

University of Auckland senior sociology lecturer Dr David Tokiharu Mayeda says when people think about migrants and what it means to be a migrant, implicit within that were migrants of colour.

“It’s diverse pacific communities, Asian communities, Middle Eastern and African communities but it’s not European communities,” Mayeda says.

“If you’re from a European background, you’re from a migrant community. Your ancestors may have been here for a long time but you’re still migrants.”

But ancestors of Pākehā migrants brought with them a level of power, enabling them to change the systems in Aotearoa to focus on economy and profit. This meant other migrant groups were working within the confines of systems created by European settlers.

Mayeda noticed this feeling of foreignness trickle into his students’ work – particularly in students with Asian backgrounds – in one assignment that required them to write about their lives.

Photo by LAWRENCE SMITH/Stuff

The Asian students who were born here or moved here when they were young wrote about distancing themselves from their family “and they will use this terminology – trying to distance themselves from FOBs (fresh off the boat)”.

More recent Asian migrants wrote about hating themselves and getting depressed about the racial stereotypes they had started to believe, he says.

Like Asian communities, Pacific communities are extremely diverse – and both umbrella ethnic communities can face being treated as “forever foreigner”, Mayeda says.

In the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, East Asians in particular were cast as virus-spreading foreign threats. That stereotype then shifted to Aotearoa’s Pacific communities in mid-2020,” Mayeda says.

“In general, however, because Pacific peoples have closer cultural connections to Māori and geographic connections to nearby Pacific nations, they tend not to be cast as foreign threats in the same way as Asians.”

Photo by LAWRENCE SMITH/Stuff

“Research I’ve been involved in shows that Pacific peoples are subjected to racism that many Māori understand – being unfairly suspected as criminogenic, lazy in school and work,” he says.

“In contrast, Asians get cast as the distant foreign threats who will take over the economy, housing market and schools if not kept in check.”

Mayeda says the country needs to recognise Māori as tangata whenua and that anyone who is not Māori, including Pākehā, comes from a migrant background.

‘All they see us as are sports stars and entertainers’

University of Auckland’s Dr Sereana Naepi says it was “very telling” how easily the rumours targeting Auckland’s Pasifika communities over the August Covid-19 cluster were believed.

One rumour suggested that a woman from a Pasifika family contracted the virus by sneaking into a managed isolation facility to see a man.

This fed into the ‘Dusky Maiden’ trope stemming from colonial times that sexualised and objectified Pacific women.

Photo by DAVID WHITE/STUFF

“People latched onto this fake story of criminals and sex,” Naepi says.

She says New Zealand’s colonising of the Pacific cemented the colonisers’ views of Pacific communities as children to be taken care of instead of strong, independent nations capable of caring for themselves.

Colonisers took on an almost paternal role so Pacific communities were incapable of being seen as a foreign threat, she adds. Full coverage

“People are happy to have Pacific communities when they benefit from their labour and cultural capital, but they’re less likely to invest in these communities.

“All they see us as are sports stars and entertainers – in their minds, we have a specific space to fill in New Zealand society.”

And when this wasn’t filled? Pacific communities were labelled as people who did not contribute, underachievers and criminals, she says.

Gatekeeping who gets to be kept in and out

Grace Gassin, a researcher and curator of Asian New Zealand histories at Te Papa Tongarewa, says “for a lot of New Zealand’s history, there’s been a desire to keep New Zealand white for lack of a better way to put it”.

“I guess we’re all dealing with the legacies of anti-Chinese discrimination and broadly, discrimination against non-whites which happened legislatively, administratively and socially,” Gassin says.

Asian migrants had been around during seminal events and there were also instances of solidarity between Māori and Asian communities – moments often quiet when New Zealand history is told, she adds.

She mentions Minnie Rose Alloo, a woman of Chinese and Scottish ancestry, as an example of this. Her signature sits neatly on a suffrage petition in 1893. She was 19 at the time of signing, making her underage.

Gassinsays the way some New Zealand history was written makes it seem like Pākehā were “colonial mediators”.

Minnie Rose Alloo’s signature on an 1893 petition sheet by Stuff Newsroom on Scribd

As the dominant group, they had a central position which meant they could determine the relationship between other ethnic groups, she says.

“Pākehā are colonisers here on this land so it’s interesting. You could argue that they’re the ultimate foreigner and migrant in the context of New Zealand history.

“But it’s often that dominant group who gets to decide who are the foreigners and gatekeep who gets to be kept in and out. They’re the ones that get to form a nation’s identity,” she says.

After the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, people could enter the country but those who were not British were considered aliens.

But throughout history, there have been barriers to prevent people – particularly those of colour – from coming to New Zealand.

In 1881, immigration restrictions were placed on Chinese people, who had to pay a poll tax to enter.

After World War I, German people, Marxists and socialists were restricted from the country.

The 1920 Immigration Restriction Amendment Act, better known as the ‘White New Zealand Policy’, made it difficult for anyone not British to come to New Zealand till the 1970s. Permission was given to people by the minister of customs.

Chinese migrants were recruited by the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce to work in the Otago goldfields. The first 12 men arrived from Australia in 1868 and by late 1869, more than 2000 Chinese men had come to the goldfields.

Pacific peoples had four waves of migration, dating back to 800-1000 years ago. The first wave was the becoming of the Māori. The second and third waves were tied to European colonisation of the Pacific with people coming to Aotearoa as trainee teachers, missionaries, sailors, whalers and civil servants. The fourth wave was linked to migration for economic reasons with Pacific peoples finding work in manufacturing and service sectors in post-war Aotearoa.

African Americans arrived to New Zealand in colonial times but mostly white people from Britain’s African colonies came in the 1870s. In the 1960s, black students came to New Zealand through study programmes.

Immigration rules meant very few black people arrived before the 1990s. In 1991, the government increased the number of refugees which saw people from Ethiopia, Rwanda, Somalia, Zimbabwe and other countries move to New Zealand.

In the late 1800s, people from Lebanon migrated to Dunedin, Wellington and Auckland. Other Middle Eastern groups that moved to New Zealand were Assyrian Christians and refugees from Iraq and Iran who arrived in the 1990s.

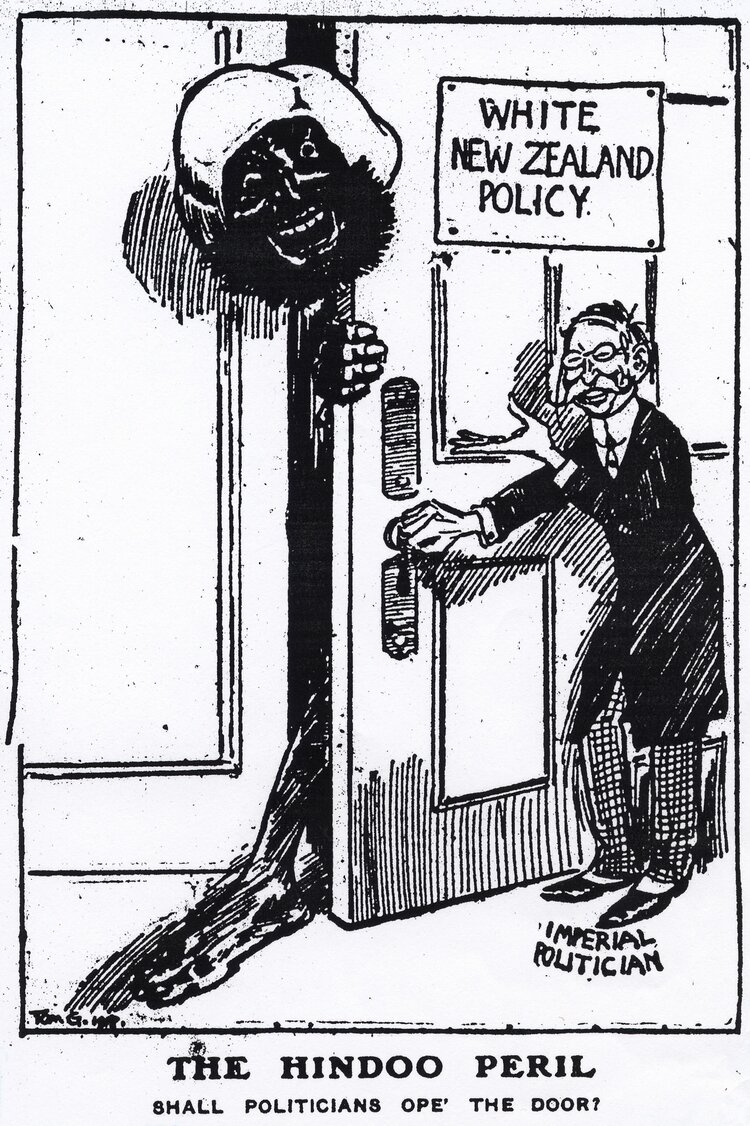

A cartoon published in Truth in 1917, shows the anti-Indian sentiment in New Zealand at that time.

A cartoon published in Truth in 1917, shows the anti-Indian sentiment in New Zealand at that time.

People from Israel, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Jordan and Bahrain moved to New Zealand in the 2000s.

People of Indian origin have been coming to New Zealand since the late 18th century. In the 1890s, Indian migration increased. Pākehā at the time lumped them with “Assyrian hawkers” and there were attempts to create laws against hawker activities and to limit their immigration.

‘There’s always a bias’

Waitakere Indian Association president Sunil Kaushal says “irrespective of whether you’re a first or second generation, there’s always a bias”.

“Indians came to New Zealand in the late 18th century and made New Zealand their home but on the flip side of it, someone who comes from Europe or America are just seen as Europeans which is just ‘normal Pākehā’,” Kaushal says.

People did not ask those of European descent where they came from, he says, which led to an underlying feeling that Indians were not considered Kiwis.

Photo by Abigail Dougherty/Stuff

In 2020, the association commissioned a report to understand the economic significance of people of Indian ethnicity in New Zealand. They found 240,000 people of Indian descent contributed $10 billion to the economy in 2019.

That number is astounding and shows how much people of Indian origin contribute to New Zealand, but they are still being put in a box and stigmatised, says Kaushal.

“Is it a myth or is it a reality? I think it’s a reality rather than a myth,” Kaushal says.

“We are Kiwis. We have given up everything to come here to be in the land of the long white cloud. This is our home.”

‘I feel it in myself’

Veena Patel has Fijian Indian and Pākehā roots, her family moved from Fiji to New Zealand when she was four following a succession of political coups in the late 80s.

When it comes to her cultural background, she says it can feel difficult to fit in or feel a part of either of them.

It’s not one moment or experience that has made her feel that way but it’s something that strikes her on a daily basis.

“When I say my name, people don’t recognise me as having my name,” Patel says.“It used to make me feel like I didn’t fit in anywhere and I wanted to minimise or hide my difference to fit in with everyone else and not be seen to be different in any way.

“As I get older and grow more mature, I’ve been able to negotiate that for myself. My identity has been a journey for me and one of discovery and I’ve been lucky enough to have my parents to explore both sides of myself.”

Patel says identity goes beyond things such as ethnicity, nationality, gender and where you live.

“Your identity and who you see yourself as, especially for culture, that’s something you get to define for yourself. Once you see that and understand that, it’s really liberating … It doesn’t matter whether people recognise me as Indian anymore because I feel it in myself.”

Patel says she feels excited for New Zealand to enter a “new era of maturity in terms of how we think about our diversity – how we think about integration as a two-way thing”.

Having a diverse background should be a source of pride, she says, it’s not something that had a bearing on whether people were Kiwi or not because it is OK to identify with more than one culture.